The vaccine babies needed others to get?

Highlights

- Rubella is generally a mild, self-limiting illness in both children and adults.

- This was the first vaccine given to benefit others rather than the recipient.

- The creation of the rubella vaccine ushered in the use of aborted human cell lines from aborted fetuses for vaccine development.

- Scientists disagreed on the likelihood of birth defects in babies of women who contracted rubella during pregnancy.

- Today’s rubella vaccine was created using cells from a fetus aborted by a mother specifically because she was exposed to rubella at eight weeks and feared the outcome, and then grown on a cell medium from another aborted baby.

- The 1965 rubella epidemic made abortion a national discussion. Once rubella was identified as a threat to a growing child in utero, conversations about abortion became medicalized and politicized.

- The rubella vaccine was rushed through on the advice of scientist who said it would prevent the next inevitable and fast-approaching rubella pandemic.

- Natural immunity seemed to disappear from the conversation once the vaccine was on the table. We find this happening in most of our shot stories.

- Studies in 1991 and 2002 found a statistically significant correlation between receiving the rubella vaccine and developing chronic arthritis.

Introduction

“German measles offers an unusual opportunity to look again at some of our current policies and ideas about disabilities, pregnancy and abortion, informed consent, vaccines, and viruses…” –Leslie J. Reagan, Dangerous Pregnancies, 2010.

No one was asking for a rubella vaccine. Rubella, which means “little red,” is not a threat to children or adults. It was known as “three-day measles” because the illness resolves itself so quickly.1 The “Modern Home Medical Advisor.” by Morris Fishbein, M.D., described it as relatively mild, without much fever in most cases, and diagnosable by the lack of serious symptoms and “the slightness of the condition.” He also stated, “The chief trouble with it is that it causes loss of time from school.”2 The MetLife insurance company assured parents, “As a rule, German measles is a mild disease with no distressing symptoms or complications.”3

So why is there a vaccine for rubella? Because a connection was made between birth defects and rubella infection during pregnancy. And that connection happened to be made during an era when medical science was rapidly expanding in the Cold War fervor of the 1950’s and 1960’s. Vaccines were a believed to be a silver-bullet solution in the ever-expanding war on illnesses.

The rubella connection ignited conversation outside of the doctor’s office. Many doctors began promoting and performing “therapeutic abortions” for mothers who feared rubella exposure in pregnancy, and thus abortion became a national debate.

Until the rubella vaccine was licensed, all vaccines were aimed at stopping illness for the recipient of the vaccine. This was the first licensed vaccine promoted to protect others.

Read on as we untangle the surprising history behind the rubella vaccine.

What is rubella?

For many years, what we now call rubella was not distinct from other rashes.4 “Discovery of disease was not a moment but rather a process.”5 The illness went by many names before the 1800s when three German scientists distinguished the illness from other rashes such as measles, and the common name of “German measles” took hold.6 Ultimately, ”children in boarding schools, orphanages, and other institutions provided opportunities for scientists to plot the disease.”7 Researchers who worked with these masses of children had sample sizes large enough to understand the subtle distinctions between illnesses and also observe that children could get measles, then get a second rash later. Knowing natural immunity prevented children from having measles again helped medical researchers identify rubella as its own illness.

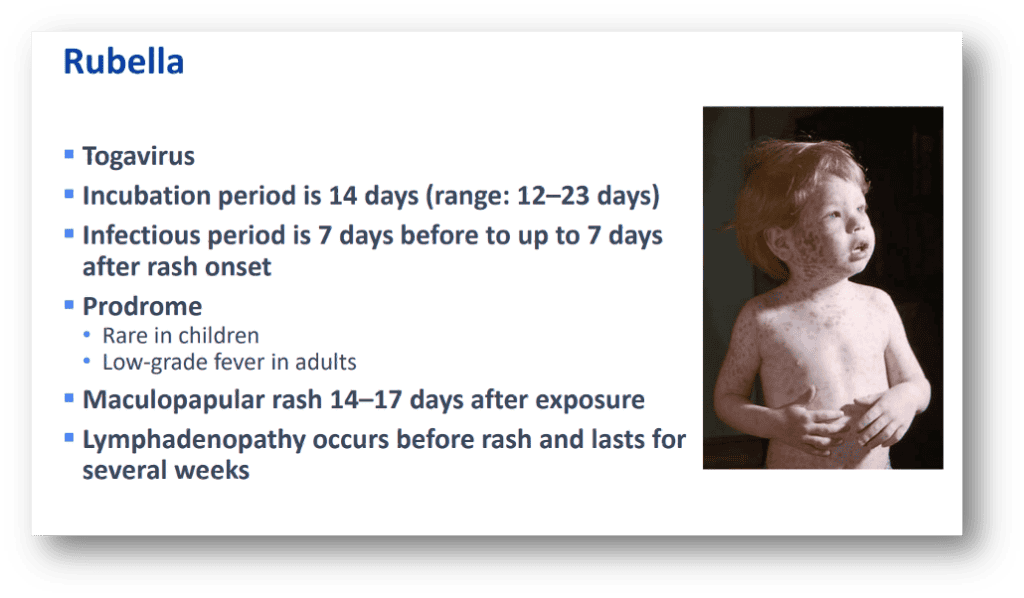

Rubella is considered a respiratory virus. Therefore, it would typically be spread via sneezing, coughing, and sharing food or drink with others. Symptoms can include low fever, headache, discomfort, swollen lymph nodes, coughing, runny nose, and mild rash.8 However, a person may have no symptoms at all. The CDC and the Lancet inform us that up to 50% of cases can be asymptomatic.9, 10

A study done in 2007 showed that contracting contagious diseases like rubella in childhood increased the body’s protective effects against coronary events like heart attacks.11 Other studies have shown that childhood infections with fever, including rubella, protect against cancer later in life.12

Complications from rubella infection at any age can include arthritis later in life and, in “rare cases,” per the CDC, brain infection or bleeding.13 The most well-known complication is miscarriage or developmental disability of the baby for pregnant women who contract the disease.

Natural infection with rubella gives lifelong immunity.14 For this reason, before there was a vaccine, parents and public health professionals alike encouraged children, especially girls before their childbearing years, to contract rubella naturally.

Rubella went from unknown to terrifying in the 1950s and ‘60s

Rubella was never, and still isn’t, a concern for children or adults. As reported by Time magazine in 1956, “To the children and adults who catch it, German measles (rubella) is almost invariably a trivial infection with slight fever, sore throat and fast-disappearing rash.”15

According to the Institute of Medicine, “Rubella … evoked little interest in the medical community until 1941, when a report appeared associating congenital cataracts (clouding of the eye’s natural lens that is present at birth) with maternal exposure to the disease during pregnancy.”16

In 1940, ophthalmologist Norman Gregg made a connection: children in his practice had mothers who had rubella during pregnancy.17

When Gregg made his observation of a correlation between eye deformations at birth and mothers recalling rubella infection, his discovery was not immediately accepted in the medical community. Medical historians say that’s because he was in Australia, which had been a remote English colony until the 1900s and thus was not taken seriously by medical elites in Europe and North America.18 Further, Gregg published his findings in a “little known, little-read medical journal” at the age of 50. He had “never published a scientific paper, was unknown to medical researchers, and … was proposing something that had never been proposed before — that a virus could cause birth defects.”19

Scientists disagreed on how likely birth defects were

Beyond lack of professional clout, there was also a question of how wide-reaching the association between rubella infection and birth defects could be. How many pregnant women were susceptible to rubella, and how often would babies become deformed because of it? There was no consensus.The Fresno Bee cited March of Dimes educational material saying 1 in 10 women hadn’t had German measles as a child.20 But it’s unclear how they would have those statistics for a disease that wasn’t nationally notifiable and is asymptomatic at least half the time. The Daily News in New York said 80% of women were immune by pregnancy, upping the estimate to around 20% of women of childbearing years susceptible.21

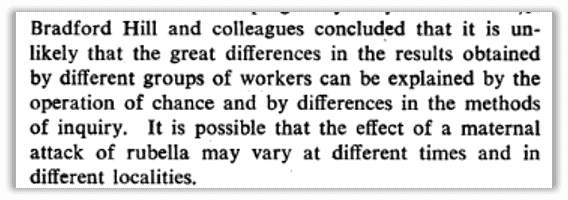

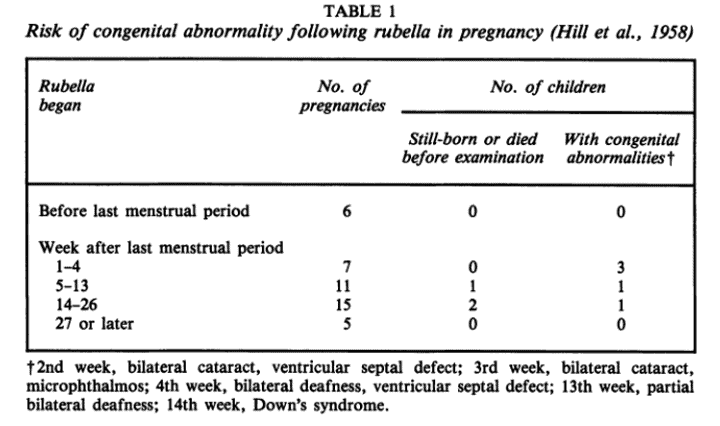

In 1958, 18 years after Gregg’s observation was published, the medical establishment was still skeptical. The British Medical Journal (BMJ) published a commentary exploring the question.22 The column reviewed published papers and found risk estimates all over the place. One researcher decided “nearly all” babies born when mothers were infected in the beginning weeks of pregnancy would be affected, another study found only 12% affected, and a handful of researchers came down between those two estimates.

This analysis was done by the best of the best. The test that epidemiologists use today to determine whether there’s a causal relationship between a presumed cause and observed effect, (in other words, whether correlation equals causation), was named after the main researcher. According to one publication, “the ’Bradford Hill Criteria’ have become the most frequently cited framework for causal inference in epidemiologic studies.”23 Therefore, it’s safe to say there was no more qualified team of researchers to observe the difficulty of how often bad fetal outcomes were linked to maternal rubella infection.

Researchers at the time had severe limitations. Cases worked backwards from the injured child to the mother’s memory of symptoms during pregnancy. This skewed the results toward higher percentages of correlation because there’s already an injured child and everyone is looking for a cause.24 It also doesn’t include any data on pregnancies where the mother recalled infection or exposure yet went on to have a healthy baby. Additionally, “the number of cases of rubella which occur during pregnancy is so small that no single series yet reported has been large enough to provide accurate estimates.”25 In other words, we get better science when we have bigger sample sizes. If there are too few cases to study, you cannot get enough data to make sweeping conclusions. Think about it: Public health officials rely on studies of a fraction of the population to make sweeping, one-size-fits-all health policy decisions like vaccine recommendations. Would it be reasonable to have a study with only eight people (or animals), draw a conclusion, and then impose that decision on over 300 million people?26 The more people you study, the less likely you are to be wrong about your conclusions.

The BMJ article concluded there was virtually no risk if a mother had rubella after her 13th week, but the risk was up to 50% if the mother had rubella in the first four weeks of pregnancy.27

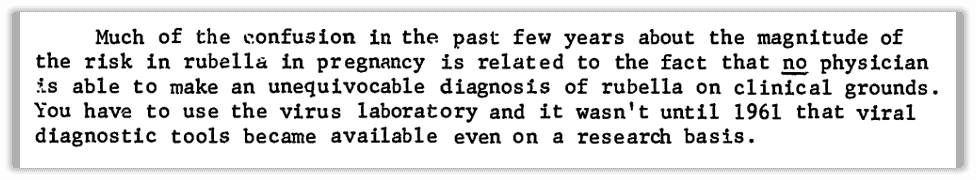

Prominent rubella doctor and researcher Dr. Louis Cooper, founder of the Rubella Project in New York, pointed out the lack of specificity of diagnosis as a challenge to assessing risk.28

He also reported:

Another medical researcher, Dr. Theodore H. Ingalls, found that the chance of pregnancy complications was much lower than most scientists believed.29

Ingalls makes a crucial point about how to read statistics. We don’t have data or information on mothers who had rubella during pregnancy yet still delivered a healthy baby. The U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (a predecessor to the Centers for Disease Control) acknowledged the same in a 1965 publication titled “Rubella”30:

This statistical debate speaks to our risk-benefit analysis. When analyzing a risk, we must look at how likely something is to happen and, if it happens, how serious can it get? And how likely is that serious outcome? What data is missing from the analysis? As you can see with the highly sensationalized situation for rubella, conservative voices in the scientific community get drowned out by the shouting of worst-case scenarios by newspapers and others who have a product to sell.

The rubella outbreak of the 1960s

The BMJ article was published in 1958, six years before the CDC was formed.The mainstream media then began reporting on the emerging medical opinion that rubella was linked to birth defects and miscarriages. The worst rubella outbreak the U.S. had seen took place in the mid-1960s, with the media now reporting that pregnant women were dangerously vulnerable. Though there had been a number of surges in rubella cases since Gregg announced the possibility for birth defects after infection in pregnancy, the “worst rubella outbreak in history” happened after a vaccine was in development.

Women were terrified, being told they were facing the possibility of an increased risk of miscarriage or giving birth to a child with developmental disability. And the mild nature of the infection became the biggest fear factor:

The options women were being pushed toward were abortion or institutionalization of a child born disabled. But no one was sure how likely it was that a child in the womb would be affected. Even two children in the same womb at the same time could have a different outcome. The choices presented to pregnant women were horrifying and heartbreaking. Doctors, as respected authority figures, were telling women to give up their babies one way or another: through abortion or institutionalization. As we have seen with measles, RSV, and mumps, institutionalization of a developmentally disabled child would not only be devastating to a family but would also leave a child vulnerable to horrific abuse through medical experimentation.32

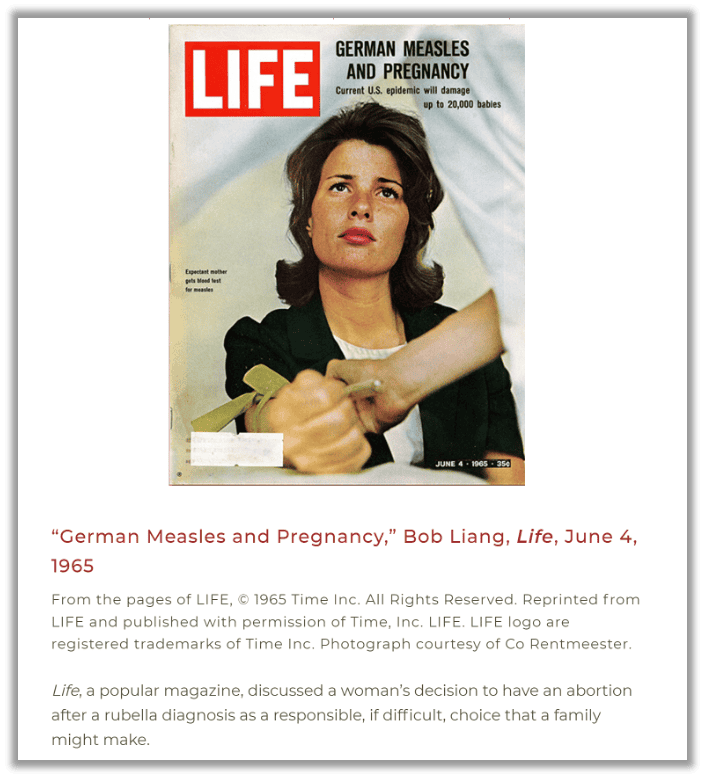

The 1965 rubella epidemic made abortion a national discussion

Once rubella was identified as a threat to a growing child in utero and a vaccine was on the horizon, conversations about abortion became medicalized and politicized.33 “[R]ubella … in the U.S., it had a profound effect on society. Abortion had been a taboo subject until then, but people began to advocate for abortion as a medical, not a moral, decision.”34

American families were scared after the thalidomide drug was linked with tragic birth defects when used off-label for morning sickness in the early 1960s.35 When an epidemic of rubella was declared in 1964, families were already primed with fear. The nuances of the scientific debate about how likely ”congenital rubella syndrome” was to occur got lost in the glare of the headlines.

According to National Geographic36:

Lawsuits against doctors for malpractice in German measles cases brought about the regular use of amniocentesis, a prenatal test that checks for birth defects in utero, as a part of prenatal care. This made “many women (and their partners) think of desired pregnancies as ‘tentative,’”37 dependent on lab tests and doctors’ opinions. This is an example of policy and money (insurance) driving medical decisions rather than patient needs, as it was understood before 1970 that amniocentesis is not very reliable for detecting a rubella infection.38

The rubella vaccine was rushed through to prevent the next pandemic

The first rubella vaccine was licensed in 1969 and combined into the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine in 1971 for use in the United States.39

Medical historian Leslie Reagan tells us in her book “Dangerous Pregnancies,” “Histories of virology and vaccine development tend to take the pressing need for a [rubella] vaccine as self-evident rather than treating it as a question.”40 The vaccine development was portrayed as a way to save women from abortions and babies from disabilities.41

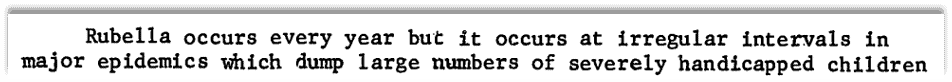

Rubella outbreaks were known to happen in surges but not all researchers believed there was cyclical predictably. Lead rubella researcher Cooper noted in 1970:

Another leading vaccine researcher was quoted in the Congressional Record testifying to the unpredictability of when the next rubella outbreak would occur:42

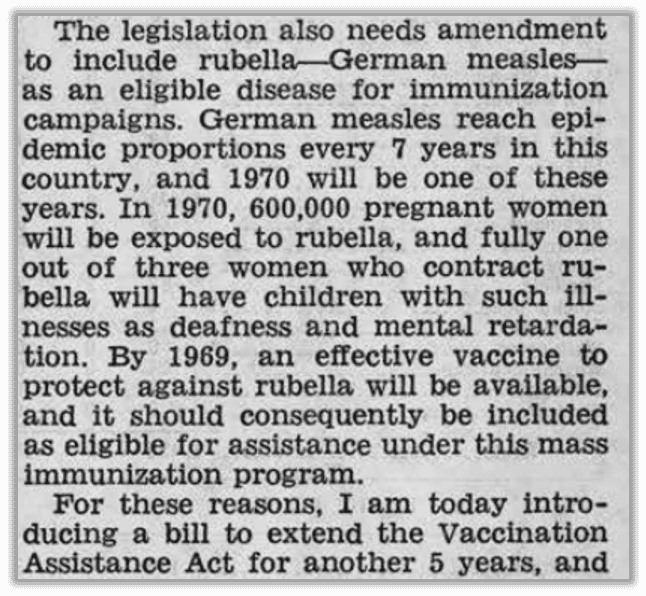

Nevertheless, vaccine researchers sold the idea that there would be another rubella epidemic in 1970. By applying the pressure and fear of the unknown, with a deadline, they were able to procure federal funds.43 Senator Edward Kennedy presented the information to Congress in support of extending the Vaccine Assistance Act, as a certainty that 1970 would see another epidemic and the claim that one third of pregnant women who “contract rubella” would have children with disabilities. Note that the vaccine for rubella had not yet been licensed when the senator spoke these words in 1968. Nevertheless, he asserted there would be an “effective vaccine to protect against rubella” in 1969 and that more funds were needed for the VAA to purchase them. Indeed, the vaccine was licensed in 1969.

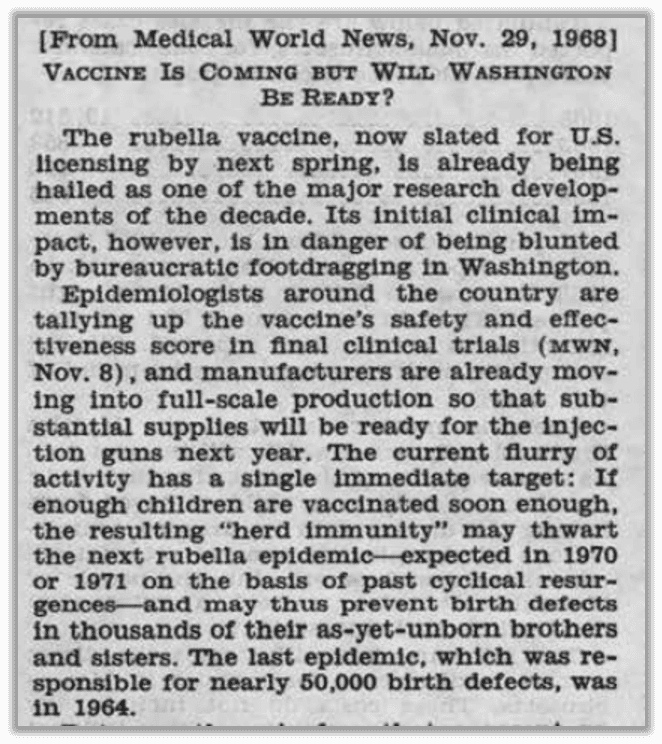

Senator Kennedy also introduced this article into the Congressional Record44 in his bid for money for a vaccine that wasn’t yet licensed, asserting the vaccine would stop the inevitable next pandemic predicted for 1970:

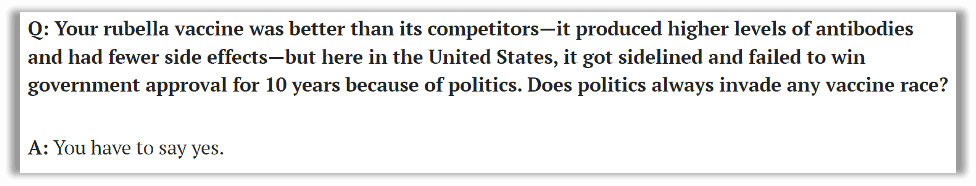

The inventor of the rubella vaccine we use today, Stanley Plotkin, known as the “Godfather of Vaccines,” who has an honorary gavel that starts ACIP meetings,45 had this to say in a recent interview about vaccine development:

Rubella vaccine development

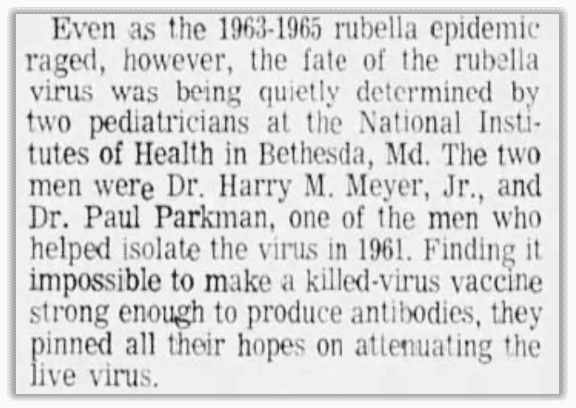

In 1914, researcher Alfred F. Hess guessed rubella was caused by a virus, based on his work with monkeys.46 But it wasn’t until 1962 that two independent groups, Paul D. Parkman and colleagues and Thomas H. Weller and Franklin A. Neva, were both credited with isolating the virus.47 Parkman worked at the U.S. Division of Biologics Standards with Harry Meyer, and they led the race to the rubella vaccine until Merck’s Maurice Hilleman stepped in.48

Hilleman learned the team had a leg up and chose to abandon work he was doing to experiment with theirs instead. As described by Paul Offit in “Vaccinated,” “Hilleman took Meyer’s virus and injected it into children living in and around Philadelphia. But he found that the virus had side effects that were intolerable. ‘I got [Meyer’s vaccine] and put it into about twenty kids and Jesus Christ, it was awful: toxic, toxic, toxic.’”49 Hilleman modified the vaccine and had it licensed for Merck in 1969. But another scientist was working on a rubella vaccine, which was ultimately embraced as the superior vaccine even by Hilleman, and became the vaccine we still use today.

Stanley Plotkin was working at the Wistar Institute in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in the 1960s. According to Offit’s “Vaccinated,” a pregnant woman came to him in 1964 for counsel, afraid she had rubella. “Plotkin advised her of the risks to her baby. A few weeks later, the fetus arrived in his laboratory.”50 He specifically chose to obtain the virus from an aborted fetus because “the fetus is in a sterile environment” and supposedly would not have other “other viruses.”51 He then grew the virus on the cell culture from another aborted fetus, and this virus strain became known as RA27/3 (rubella [from] aborted fetus 27/3rd organ harvested).52

Plotkin happened to work at the same institute that employed Leonard Hayflick, a scientist studying aging who became famous for observing the limited number of times a cell will divide (known as the Hayflick Limit). Hayflick obtained fetal cells from Sweden and passed them on to Plotkin for his vaccine experiments. The source of the Swedish cells was a woman who reportedly did not want any more children because her husband was a “drunkard” so she obtained an abortion at three months.

Background on use of aborted fetal cell lines in vaccine research and development

The vaccine we still use today for rubella was created using cells from a fetus aborted by a mother during the rubella epidemic specifically because she was exposed to rubella at eight weeks and feared the outcome., It was grown on fetal cells from another aborted fetus.

Why are aborted fetal cells used in vaccine research and development? To “grow” viruses to manufacture vaccines, you need something to grow them in. When vaccine research began, that host was animal tissue. But that can be highly problematic if the virus won’t grow. There can also be unknown contaminants, as the world learned when SV-40 was found in the polio vaccines.

The use of animals to create vaccines has been problematic since the beginning. Animals have been used to harvest illness (as in the case of cowpox), to grow toxoids such as tetanus and diphtheria, and killed to use organs as cell cultures for growing viruses. Animal products are used as well, such as chicken eggs to grow influenza vaccine.

Contamination of the end product is only one of the challenges researchers face when using animals. Another issue is cost. They require space and manpower to handle and, in the case of animal products such as eggs, are at the whim of the supply. And to the displeasure of scientists, some pathogens do not grow well in animal cells.

For these reasons, fetal cell lines are considered the “gold standard” for pharmaceutical development. (Note that fetal cell lines are not exclusive to the vaccine industry; other drugs, such as Regeneron’s antibody treatment for COVID-19, used fetal cells in development.)

Rubella vaccines were initially developed in duck embryo and dog kidney cells. Plotkin used fetal cells to isolate the virus, and to grow it. His vaccine was ultimately deemed the best for efficacy and safety reasons and therefore was incorporated into Merck’s MMR shot.

From the pioneer in the field of fetal cell research and creator of the WI-38 cell line, Leonard Hayflick53:

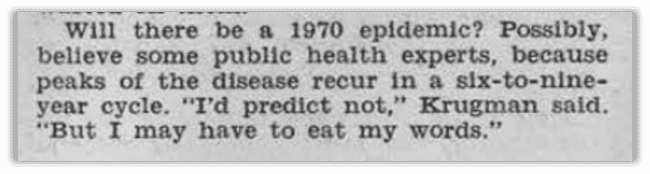

TABLE: Human fetal cell lines used in childhood vaccine research and development

| Name | Stands for | Researcher | Source | Age | Abortion reason | Year | Other | Used to make |

| RA 27/354 | Rubella Attenuated, 27th fetus, 3rd tissue removed | Stanley Plotkin, Wistar Institute, Philadelphia, PA | Fetal kidney | Est. 9 weeks | Rubella infection during early pregnancy | 1964 | 25-year-old mother | Rubella |

| WI-3855 56 | Wistar Institute- 38th fetus. | Leonard Hayflick | Female fetal lung | Approx. 3 months | Legal abortion in Sweden. Married parents, healthy pregnancy, father alcoholic, so mom did not want more kids.57 | 196258 | Mom did not consent, nor have knowledge of the use. Hayflick widely shared these cells around the world. | Rubella |

| MRC-559 60 61 62 63 | Medical Research Center (UK) | J.P. Jacobs | Male fetal lung | 14 weeks | “Psychiatric reasons” | 1966 | 27-year-old healthy mom | Varicella, Hepatitis A |

| HEK-29364 65 | Human embryonic kidney cells, 293rd experiment (Netherlands) | Frank Graham, in Alex Van der Eb’s lab | Fetal kidney | unknown | Unknown (records lost and scientist doesn’t recall). Legal “therapeutic abortion” likely due to illegality of abortion, health of fetal cells, and doctor’s typical practices. | Cells obtained 1972, cell line made 1973 | Note 293rd experiment does not equal 293 fetuses. Baby was healthy. One of the most used cell lines in the world. | COVID (production of AZ; R&D for Pfizer, Moderna) |

| PER.C6 6667 68 | Peripheral eye retina, Crucell (biotech developer), 6th clone. | Ron Bout and Frits Fallsux in Alex Van der Eb’s lab | Fetal retina | 18 weeks | “Socially indicated” for “unknown father.” Healthy baby, psychologically “normal” mother. | Cells frozen 1985,cell line made 1995. | Van der Eb told the FDA, “There was permission, et cetera.” Used widely in gene therapy. Adenovirus transformed the fetal retinal cells. | COVID (Janssen) |

Exemptions due to objection to abortion

Many people have a moral and religious objection to using a product that has utilized fetal cells from abortions. This is a main driver for religious exemptions. But Catholics, for example, get pushback on their exemption because the Catholic Church supports the use of vaccines made from aborted fetal cell lines. The pushback is out of line, however, because our constitutional rights are not dependent on which faith we follow or whether we agree with all the dogma. A person can assert a valid religious exemption to any vaccine based on objection to abortion, regardless of what their church holds, or even if they don’t belong to any church at all. The simple assertion of a sincerely held belief is all that is required. It’s notable that if a person were to volunteer details about their beliefs, that their exemption could be limited only to those vaccines that use fetal cell lines. You can learn more about religious exemptions in our Health Freedom Institute Foundations course.

Rubella was the first vaccine given to protect someone else

It was widely understood that rubella was not a threat to children or adults. The potential threat was for the unborn, who could not be vaccinated. Therefore, the only way to use a vaccine to stop rubella in the womb was to stop the susceptibility of the mother to the illness, preventing exposure. The vaccine had to be given to those who were not at risk of serious illness to create herd immunity for those who could not be vaccinated. This concept was new, and it’s another way the rubella vaccine changed social discourse and public attitudes. Until the rubella vaccine was licensed, all vaccines were aimed at stopping illness for the recipient of the vaccine.

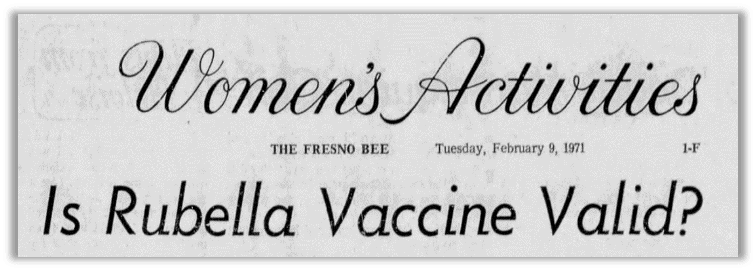

There was public disagreement over the validity of mass immunization of children for rubella.

Could you imagine a headline like this nowadays about any of the multitude of vaccines coming to market? The article reported:

The article explained:

Dr. Louis Cooper criticized the ACIP approach to simply vaccinating all children, pointing out different potential approaches in his paper, “Rubella, Developmental Problems and Family Health Services,” in 1970.69

Cooper echoed the public concern on how long immunity would last from a vaccine and pointed out that even scientists didn’t know what percentage of people needed to be vaccinated to create herd immunity. He compared the European approach to vaccinating 13-year-old girls who were “captive” in school and on the verge of childbearing years, so their maternal immunity would protect their future babies.

Relying on natural immunity seemed to disappear from the conversation once the vaccine was on the table. Testing for rubella antibodies was possible after the virus was isolated and tests improved by the time the vaccine was available.70 What if, instead of a recommendation to vaccinate all children with a shot they didn’t need for themselves, the U.S. Public Health Service had recommended all women of childbearing age get tested for their immunity?

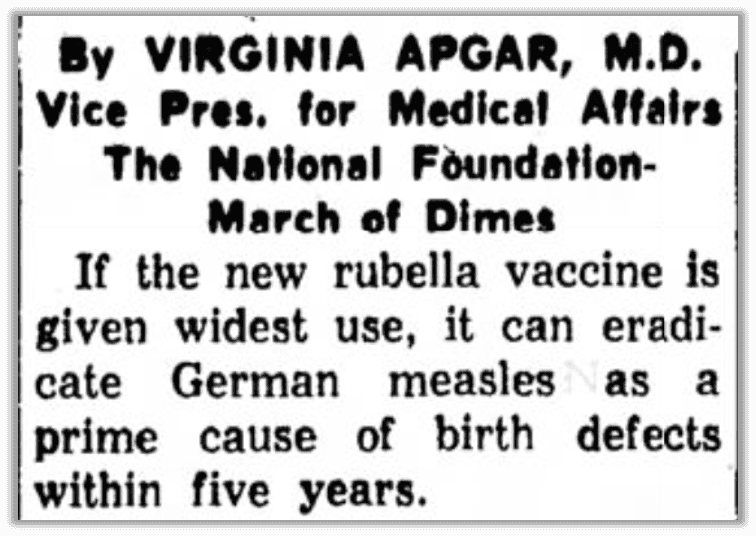

In fact, Dr. Virginia Apgar, Vice President of Medical Affairs of the March of Dimes, advocated for premarital blood tests for rubella.71 Premarital blood test laws were once common, though turning out of fashion, and generally targeted sexually transmitted diseases.72

To be sure, Apgar was also a proponent of the vaccine. Regardless of the uncertainties and alternatives, as Cooper put it, “I don’t know who’s right. No one knows for sure. In practical terms, since the Committee on Immunization Practices after much discussion has decided this is the route we’ll go, this is the route we have to go.” That is, frankly, a shockingly defeatist statement from a lead doctor and researcher in one of the most important fields of the time, to bow to the decision of a panel created just six years earlier.73

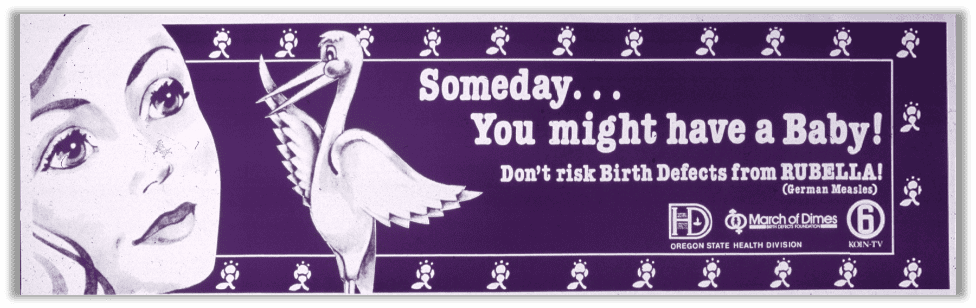

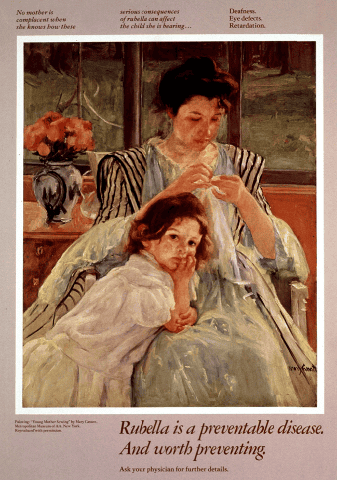

A massive campaign was designed to convince parents to vaccinate their children since the vaccine was being promoted for the “greater good,” messaging had to appeal to the morality of having a responsibility toward others, either as a mother or as a member of a community.

The March of Dimes went door to door:74

Health departments across the country promoted the vaccine for schoolchildren and young women, in particular.

Promotions of the vaccine were not just targeted at adults. Specific campaigns were created to emotionally incite children to protect the adults around them, as well as the next generation. Vaccinators would incentivize children to get the shot by giving out medals or stickers the children could wear to show they followed the rules (and simultaneously announce their vaccination status).

Efficacy

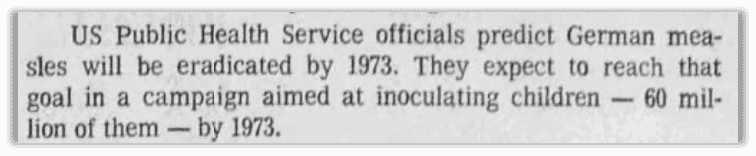

As with the measles vaccine, immediately upon licensing, some public health experts were hailing it as the way to wipe out the disease quickly.

The Fresno Bee reported in 197175:

“Rubella epidemics usually strike in cycles of six to nine years.”76 Since the last epidemic was in 1963 and 1964, researchers believed the next cycle would be around 1970. In what seems to be more common than not, researchers raced to create a rubella vaccine before the predicted epidemic.77

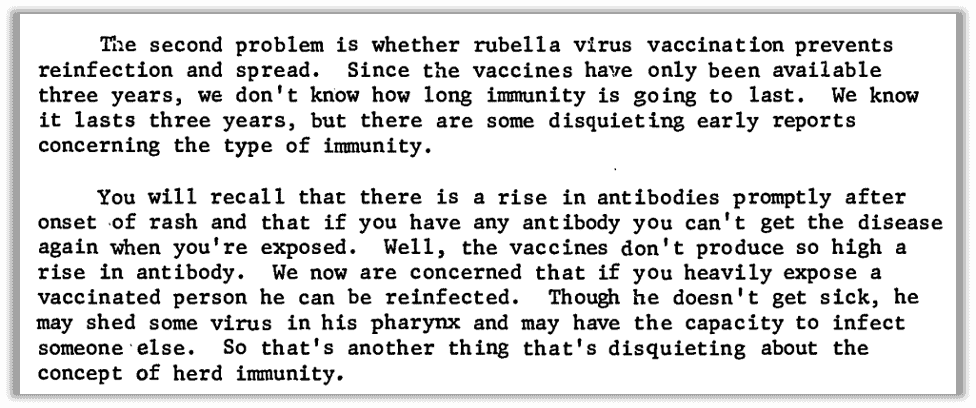

From Louis Cooper78:

In 1978, a publication titled “Epidemic Rubella in Military Recruits” described the constant flow of cases of rubella at a military base, which would surge with new recruits, despite high levels of vaccination at 89.1%.79 The conclusion was that herd immunity for rubella would only work if everyone was vaccinated. It wasn’t stated whether those who were deemed to have rubella had been vaccinated.

F.T Perkins from the World Health Organization noted in 1985, “It is clear that the antibody response to any rubella vaccine is lower than that to natural infection.”80

In 2005 rubella was declared eliminated in the United States by the CDC.

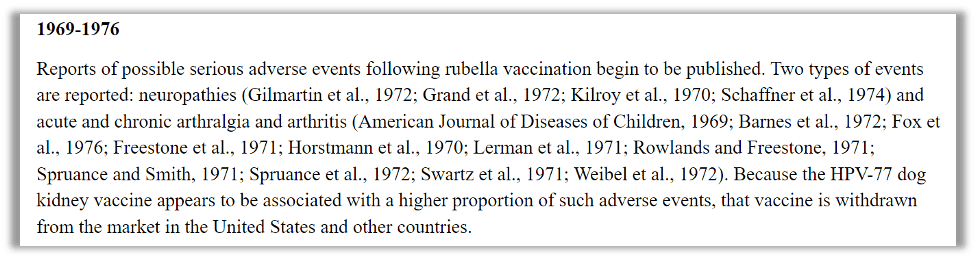

Risks of rubella vaccine

Shortly after the introduction of the rubella vaccine, there were reports of arthritis or joint pain, especially in women. As reported by the Institute of Medicine:81

The Institute of Medicine did a comprehensive analysis of the possibility of adverse events after rubella vaccine, published in 1991.82 It was found that there was a correlation between chronic arthritis and vaccine administration.

A 2002 study showed a statistically significant association with the hepatitis B and rubella vaccines with chronic arthritis.83

Conclusion

Similar to mumps and measles, there was no public outcry or urgent need for a rubella vaccine. That changed when doctors associated the mild illness with an unknown and uncertain risk of birth defects. Suddenly, vaccination was no longer about protecting individuals to stop the spread of disease, it became a community responsibility toward the next generation. The rubella vaccine changed the landscape of public health and ignited social activism in the areas of birth and disability.

REFERENCES

- Lanzieri, Tatiana MD., et al. “Rubella.” CDC Pinkbook 14th edition, (2021). https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/rubella.html#:~:text=Rubella%20and%20congenital%20rubella%20syndrome%20became%20nationally%20notifiable%20diseases%20in%201966. ↩︎

- Fishbein, Morris. 1942. Modern Home Medical Advisor: Your Health and How to Preserve It. New York: Doubleday, Doran & Company, Inc. page 254. ↩︎

- “Common Childhood Diseases.” Metropolitan Life Insurance Company, November 1954. ↩︎

- Lanzieri, Tatiana MD., et al. “Rubella.” CDC Pinkbook 14th edition, (2021). https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/rubella.html#:~:text=Rubella%20and%20congenital%20rubella%20syndrome%20became%20nationally%20notifiable%20diseases%20in%201966. ↩︎

- Reagan, Leslie J. 2012. Dangerous Pregnancies: Mothers, Disabilities, and Abortion in Modern America. 1st ed. University of California Press. p 24. ↩︎

- Cooper, L Z. “The History and Medical Consequences of Rubella.” Reviews of Infectious Diseases. Mar-Apr (1985). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3890105/. ↩︎

- Reagan, Leslie J. 2012. Dangerous Pregnancies: Mothers, Disabilities, and Abortion in Modern America. 1st ed. University of California Press. page 27. ↩︎

- “Rubella Symptoms and Complications.” https://www.cdc.gov/rubella/signs-symptoms/index.html. ↩︎

- Winter, Amy K., Moss, William J. “Rubella.” The Lancet, (2022). https://www.thelancet.com/clinical/diseases/rubella. ↩︎

- Lanzieri, Tatiana MD., et al. “Rubella.” CDC Pinkbook 14th edition, (2021). https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/rubella.html#:~:text=Rubella%20and%20congenital%20rubella%20syndrome%20became%20nationally%20notifiable%20diseases%20in%201966. ↩︎

- Miller, Neil Z. 2016. Miller’s Review of Critical Vaccine Studies. 1st ed. New Atlantean Press. page 150, study 180 by Pesonen.. ↩︎

- Miller, Neil Z. 2016. Miller’s Review of Critical Vaccine Studies. 1st ed. New Atlantean Press. page 235 citing Albonico, page 238 citing Alexander, p 239 citing Glaser ↩︎

- “Rubella Symptoms and Complications.” https://www.cdc.gov/rubella/signs-symptoms/index.html. ↩︎

- “Rubella.” Internet Archive (U.S. Dept. of Health, Education, and Welfare), August 1, 1965. https://archive.org/details/rubella00unit/mode/2up ↩︎

- “Medicine: Catch German Measles.” Time, December 31, 1956. https://content.time.com/time/subscriber/article/0,33009,867505,00.html. ↩︎

- “Pertussis and Rubella Vaccines: A Brief Chronology.” National Library of Medicine. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK234365/. ↩︎

- “Our greatest medical discovery.” The Sydney Morning Herald (Sydney, AU), August 5, 1951. page 9. ↩︎

- Reagan, Leslie J. 2012. Dangerous Pregnancies: Mothers, Disabilities, and Abortion in Modern America. 1st ed. University of California Press. page 42 ↩︎

- Offit, Paul A. MD. 2022. Vaccinated: From Cowpox to MRNA, the Remarkable Story of Vaccines. Harper Perennial. page 70. ↩︎

- Koch, Linda. “Is Rubella Vaccine Valid?” The Fresno Bee (Fresno, CA), February 9, 1971. page 37. ↩︎

- Shiller, Alice. “Rubella Strikes the Young but Should Concern All.” Daily News (New York, NY), September 17, 1971. page 9. ↩︎

- “Virus Diseases in Pregnancy.” British Medical Journal 2, no. 5102 (1958): 962–963. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25385335. ↩︎

- Fedak KM, Bernal A, Capshaw ZA, Gross S. Applying the Bradford Hill criteria in the 21st century: how data integration has changed causal inference in molecular epidemiology. Emerg Themes Epidemiol. 2015 Sep 30;12:14. doi: 10.1186/s12982-015-0037-4. PMID: 26425136; PMCID: PMC4589117. ↩︎

- Ober, R. E. MD, et al. “Congenital Defects in a Year of Epidemic Rubella.” American Journal of Public Health 37, no. 10 (1947): 1328-1333. https://sci-hub.st/10.2105/ajph.37.10.1328. ↩︎

- “Virus Diseases in Pregnancy.” British Medical Journal 2, no. 5102 (1958): 962–963. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25385335. ↩︎

- Swanson, Kena A. PhD. “Pfizer/BioNTech COVID-19 Omicron-Modified Vaccine Options.” PowerPoint slides, June 8, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/media/159496/download ↩︎

- “Virus Diseases in Pregnancy.” British Medical Journal 2, no. 5102 (1958): 962–963. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25385335. ↩︎

- “Current Issues in Mental Retardation.” Selected Papers from the 1970 Staff Development Conferences of The President’s Committee on Mental Retardation. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED052577.pdf. ↩︎

- Williams, Greer. “Virus Hunters.” Internet Archive, (1960). https://archive.org/details/virushunters0000unse/mode/2up. page 325. ↩︎

- “Rubella.” Internet Archive (U.S. Dept. of Health, Education, and Welfare), August 1, 1965. https://archive.org/details/rubella00unit/mode/2up. ↩︎

- Liang, Bob. “German Measles and Pregnancy:.” Life, June 4, 1965. https://www.nlm.nih.gov/exhibition/rashestoresearch/collection-detail.html?imgid=15&imgName=OB12723-md. ↩︎

- Hornblum, Allen M., Judith L. Newman, and Gregory J. Dober. 2013. Against Their Will: The Secret History of Medical Experimentation on Children in Cold War America. 1st ed. St. Martin’s Press. ↩︎

- Little, Becky. “Way Before Zika, Rubella Changed Minds on Abortion.” National Geographic https://web.archive.org/web/20170422130925/http://news.nationalgeographic.com/2016/02/160205-zika-virus-rubella-abortion-brazil-birth-control-womens-health-history/. ↩︎

- Little, Becky. “Way Before Zika, Rubella Changed Minds on Abortion.” National Geographic https://web.archive.org/web/20170422130925/http://news.nationalgeographic.com/2016/02/160205-zika-virus-rubella-abortion-brazil-birth-control-womens-health-history/. ↩︎

- Little, Becky. “Way Before Zika, Rubella Changed Minds on Abortion.” National Geographic https://web.archive.org/web/20170422130925/http://news.nationalgeographic.com/2016/02/160205-zika-virus-rubella-abortion-brazil-birth-control-womens-health-history/. ↩︎

- Little, Becky. “Way Before Zika, Rubella Changed Minds on Abortion.” National Geographic https://web.archive.org/web/20170422130925/http://news.nationalgeographic.com/2016/02/160205-zika-virus-rubella-abortion-brazil-birth-control-womens-health-history/. ↩︎

- Little, Becky. “Way Before Zika, Rubella Changed Minds on Abortion.” National Geographic https://web.archive.org/web/20170422130925/http://news.nationalgeographic.com/2016/02/160205-zika-virus-rubella-abortion-brazil-birth-control-womens-health-history/. ↩︎

- “Current Issues in Mental Retardation.” Selected Papers from the 1970 Staff Development Conferences of The President’s Committee on Mental Retardation. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED052577.pdf. (page 93 of the document). ↩︎

- Lanzieri, Tatiana MD., et al. “Rubella.” CDC Pinkbook 14th edition, (2021). https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/rubella.html#:~:text=Rubella%20and%20congenital%20rubella%20syndrome%20became%20nationally%20notifiable%20diseases%20in%201966. ↩︎

- Reagan, Leslie J. 2012. Dangerous Pregnancies: Mothers, Disabilities, and Abortion in Modern America. 1st ed. University of California Press. page 3. ↩︎

- Reagan, Leslie J. 2012. Dangerous Pregnancies: Mothers, Disabilities, and Abortion in Modern America. 1st ed. University of California Press. page 19. ↩︎

- Congress.gov. “Congressional Record.” June 26, 2024. https://www.congress.gov/bound-congressional-record/1969/02/19/115/house-section/article/3964-4030. page 4003. ↩︎

- Congress.gov. “Congressional Record.” June 26, 2024. https://www.congress.gov/bound-congressional-record/1966/09/27/112/senate-section/article/23858-23944. page 23922 ↩︎

- Congress.gov. “Congressional Record.” June 26, 2024. https://www.congress.gov/bound-congressional-record/1966/09/27/112/senate-section/article/23858-23944. page 6948 ↩︎

- “United States. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. “Meeting of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), October 25-26, 2017, Summary Minutes” (2017).” https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/157578. ↩︎

- Lanzieri, Tatiana MD., et al. “Rubella.” CDC Pinkbook 14th edition, (2021). https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/rubella.html#:~:text=Rubella%20and%20congenital%20rubella%20syndrome%20became%20nationally%20notifiable%20diseases%20in%201966. ↩︎

- Cooper L. Z. (1985). The history and medical consequences of rubella. “Reviews of infectious diseases.” 7 Suppl 1, S2–S10. https://doi.org/10.1093/clinids/7.supplement_1.s2 ↩︎

- Offit, Paul A. MD. 2022. Vaccinated: From Cowpox to MRNA, the Remarkable Story of Vaccines. Harper Perennial. page 74. ↩︎

- Offit, Paul A. MD. 2022. Vaccinated: From Cowpox to MRNA, the Remarkable Story of Vaccines. Harper Perennial. page 77. ↩︎

- Offit, Paul A. MD. 2022. Vaccinated: From Cowpox to MRNA, the Remarkable Story of Vaccines. Harper Perennial. page 82. ↩︎

- Offit, Paul A. MD. 2022. Vaccinated: From Cowpox to MRNA, the Remarkable Story of Vaccines. Harper Perennial. page 82. ↩︎

- Offit, Paul A. MD. 2022. Vaccinated: From Cowpox to MRNA, the Remarkable Story of Vaccines. Harper Perennial. page 83. ↩︎

- Hayflick, Leonard. “A Novel Technique for Transforming the Theft of Mortal Human Cells into Praiseworthy Federal Policy.” ResearchGate, January 1, 1998. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Leonard-Hayflick/publication/13762615_A_novel_technique_for_transforming_the_theft_of_mortal_human_cells_into_praiseworthy_federal_policy/links/5ac52a1a0f7e9b1067d4bdbe/A-novel-technique-for-transforming-the-theft-of-mortal-human-cells-into-praiseworthy-federal-policy.pdf. ↩︎

- Plotkin, S.A. “Studies of Immunization With Living Rubella Virus.” American Journal of Diseases of Children 110, no. 4 (1965): 381. ↩︎

- Gorvett, Zaria. “The Controversial Cells that Saved 10 Million Lives.” BBC, November 4, 2020. https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20201103-the-controversial-cells-that-saved-10-million-lives.

“MMR II Package Insert.” https://www.fda.gov/media/75191/download?attachment. ↩︎ - “M-M-R II Package Insert.” https://www.fda.gov/media/75191/download?attachment.”The Controversial Cells that Saved 10 Million Lives.” BBC, November 4, 2020. https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20201103-the-controversial-cells-that-saved-10-million-lives.

“MMR II Package Insert.” https://www.fda.gov/media/75191/download?attachment. ↩︎ - Hayflick, Leonard. “A Novel Technique for Transforming the Theft of Mortal Human Cells into Praiseworthy Federal Policy.” ResearchGate, January 1, 1998. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Leonard-Hayflick/publication/13762615_A_novel_technique_for_transforming_the_theft_of_mortal_human_cells_into_praiseworthy_federal_policy/links/5ac52a1a0f7e9b1067d4bdbe/A-novel-technique-for-transforming-the-theft-of-mortal-human-cells-into-praiseworthy-federal-policy.pdf. ↩︎

- Hayflick, Leonard. “A Novel Technique for Transforming the Theft of Mortal Human Cells into Praiseworthy Federal Policy.” ResearchGate, January 1, 1998. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Leonard-Hayflick/publication/13762615_A_novel_technique_for_transforming_the_theft_of_mortal_human_cells_into_praiseworthy_federal_policy/links/5ac52a1a0f7e9b1067d4bdbe/A-novel-technique-for-transforming-the-theft-of-mortal-human-cells-into-praiseworthy-federal-policy.pdf. ↩︎

- “MRC-5 – Normal Human Fetal Lung Fibroblast.” Coriell Institute for Medical Research. https://catalog.coriell.org/0/Sections/Search/Sample_Detail.aspx?Ref=AG05965-D. ↩︎

- “PRIORIX Package Insert.” https://www.fda.gov/media/158941/download?attachment. ↩︎

- “HAVRIX Package Insert.” https://www.fda.gov/media/119388/download?attachment. ↩︎

- “VAQTA Package Insert.” https://www.fda.gov/media/74519/download?attachment. ↩︎

- “VARIVAX Package Insert.” https://www.fda.gov/media/76008/download?attachment. ↩︎

- Couronne, Ivan. “How fetal cells from the 1970s power medical innovation today.” Medial Xpress, October 20, 2020. https://medicalxpress.com/news/2020-10-fetal-cells-1970s-power-medical.html ↩︎

- FDA VRBPAC Transcript. Wednesday, May 16, 2001. https://wayback.archive-it.org/7993/20170404095417/https://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/01/transcripts/3750t1_01.pdf ↩︎

- Couronne, Ivan. “How fetal cells from the 1970s power medical innovation today.” Medial Xpress, October 20, 2020. https://medicalxpress.com/news/2020-10-fetal-cells-1970s-power-medical.html ↩︎

- FDA VRBPAC Transcript. Wednesday, May 16, 2001. https://wayback.archive-it.org/7993/20170404095417/https://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/01/transcripts/3750t1_01.pdf ↩︎

- Zimmerman, Richard K. “Helping patients with ethical concerns about COVID-19 vaccines in light of fetal cell lines used in some COVID-19 vaccines.” Vaccine. 2021 Jul 13; 39(31): 4242-4244. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8205255/ ↩︎

- “Current Issues in Mental Retardation.” Selected Papers from the 1970 Staff Development Conferences of The President’s Committee on Mental Retardation. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED052577.pdf. ↩︎

- Cradock-Watson, J.E. “Laboratory Diagnosis of Rubella: Past, Present and Future.” Epidemiol. Infect., no. 107 (1991): 1-15. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2272022/pdf/epidinfect00028-0025. ↩︎

- Apgar, Virginia MD. “Vaccine Can Wipe Out Major Birth Defect Cause.” The Ludington Daily News (Ludington, MI), December 19, 1969. page 2. ↩︎

- Shafer, JK. Premarital health examination legislation; history and analysis. Public Health Rep (1896). 1954 May;69(5):487-93. PMID: 13167271; PMCID: PMC2024341. ↩︎

- Sekar, Kavya. “The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP).” Congressional Research Service: In Focus, February 2, 2023. https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/IF12317.pdf. ↩︎

- Koch, Linda. “Is Rubella Vaccine Valid?” The Fresno Bee (Fresno, CA), February 9, 1971. page 37. ↩︎

- Koch, Linda. “Is Rubella Vaccine Valid?” The Fresno Bee (Fresno, CA), February 9, 1971. page 37. ↩︎

- Apgar, Virginia MD. “Vaccine Can Wipe Out Major Birth Defect Cause.” The Ludington Daily News (Ludington, MI), December 19, 1969. page 2. ↩︎

- Carper, Jean. “Campaign against Rubella a Medical Success Story.” Corpus Christi Caller-Times (Corpus Christi, TX), April 26, 1970. page 20. ↩︎

- “Current Issues in Mental Retardation.” Selected Papers from the 1970 Staff Development Conferences of The President’s Committee on Mental Retardation. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED052577.pdf. ↩︎

- Gremillion, Maj. David H., et al. “Epidemic Rubella in Military Recruits.” Southern Medical Journal 71, no. 8 (1978): 932-934. https://www.wellesu.com/10.1097/00007611-197808000-00019. ↩︎

- Perkins, F.T. “Licensed Vaccines.” Reviews of Infectious Diseases 7, (1985): S73-S76. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4453597. ↩︎

- “Pertussis and Rubella Vaccines: A Brief Chronology.” National Library of Medicine. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK234365/. ↩︎

- Howson, Christopher P., et al. “Adverse Effects of Pertussis and Rubella Vaccines.” Institute of Medicine, (1991). https://www.google.com/books/edition/Adverse_Effects_of_Pertussis_and_Rubella/9QGfAwAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=evoked+little+interest+in+the+medical+community+until+1941,+when+a+report+appeared+associating+congenital+cataracts+with+maternal+exposure+to+the+disease+during+pregnancy&pg=PT34&printsec=frontcover. ↩︎

- Miller, Neil Z. 2016. Miller’s Review of Critical Vaccine Studies. 1st ed. New Atlantean Press. page 169 A ↩︎