An illness virologists wanted children to get.

Editor’s note: This article is about mumps alone. The combination MMR shot will be discussed separately.

Highlights

- Before the mumps vaccine, an estimated 95% of Americans had mumps in childhood, many asymptomatic, and the illness was rarely fatal.

- Many studies have shown a history of childhood mumps could protect against various cancers and coronary events later in life.

- One of the pioneers in the field of virology was a proponent of intentional exposure to mumps and rubella to induce natural immunity and avoid complications from infection later in life.

- It is widely accepted in the medical community that the efficacy of the mumps vaccine is questionable at best.

- If our vaccines don’t last very long, we’re creating a situation where vaccination is less safe overall, and riskier than acquiring the disease naturally.

- Mumps vaccine safety has been so frequently questioned that Japan removed it from their recommended immunizations.

If you could remove every pain, heartache, illness, and mistake your child might endure, would you? It’s tempting to want to say yes. But that loving desire to shield your child from life’s struggles may be a reflection your own fears and discomfort in seeing them grapple with challenge. Consider this: What if life’s challenges are exactly what they need to make them stronger?

Before development of the mumps vaccine, it was estimated that 95% of Americans were exposed to mumps in childhood, generally without complications, and the illness was “rarely fatal.”1 In fact, the CDC didn’t start tracking mumps as a notifiable disease until after the vaccine was developed.2 (By comparison, measles became a nationally notifiable disease in 1912, 50 years before vaccine development).3

Because the mumps infection was so mild, and acquiring the illness later in life was much more dangerous, public health officials advocated for “mumps parties” to make sure children went through the illness young.

So why, suddenly, did we want to stop the disease?

Read on to find out.

What is the illness known as mumps?

Mumps is considered a virus that causes swelling in the neck between the ear and the jaw (in the salivary glands), sore throat, earache, muscle aches, headache, and low fever.4 The CDC states that the incubation period is 12-25 days. Complications are more likely in adults than in children. Spread through respiratory droplets and saliva, it’s considered infectious from two days prior to swelling in the throat through five days after. According to the CDC, “Before the introduction of the mumps vaccine, approximately 15% to 24% of infections were asymptomatic.”5 In other words, up to a quarter of people who were infected with mumps had no symptoms at all.

Mumps is in a family of identified viruses called paramyxoviruses, which “comes from the Greek ‘para,’ meaning ‘by the side of,’ and ‘myxa’ meaning mucus.”6 Measles is in the same category. Two researchers at Vanderbilt University Medical School in Tennessee, with grants from the Rockefeller Foundation and the Josiah Macy, Jr. Foundation, are credited with determining that mumps is caused by a virus.7 They took saliva from patients diagnosed with mumps and injected it into the salivary glands of monkeys, some of whom then showed signs of mumps. They killed the sick monkeys, removed their swollen glands, ground them up, and injected them into more monkeys. They repeated this for seven generations, and thus concluded they had a “filterable agent” from the initial saliva taken from sick people, declaring they discovered a virus that caused mumps.

The “filterable agent” practice was the standard way researchers at the turn of the 20th century looked for an external cause for illnesses. A filter was used that was so fine that bacteria (which could be seen under a microscope) could not pass through. Scientists reasoned, if illness could be generated by the remaining liquid, there must be an agent that made it through the filter that caused illness. These “microbe hunters” were searching for a thing they could target with a cure they would develop. In the essay “Inventing Viruses,” Yale medical researcher William C. Summers describes: “Viruses became known by a property that was absent: culturability. Soon another absent property was added to the description of viruses: visibility.” 8 In other words, viruses were defined by declaring they existed when scientists didn’t see anything. The word “virus” is commonly understood to derive from the Latin word for poison. The filterable agent started being referred to as a “filterable virus” (a poisonous liquid), and ultimately “virus” alone was adopted as the term for the thing they had been searching for, as scientists used newly invented electron microscopes to observe objects they expected to see and advanced techniques of filtration to estimate size of their object of study.9 With these technologies, the concept of “virus” literally and figuratively took shape.

Even though the researchers Claud Johnson and Ernest Goodpasture attributed mumps to a virus, scientists still had nothing to point to other than a slurry that made animals and people sick. In 1945, however, a researcher at the U.S. Public Health Service declared that the virus had been isolated, setting the stage for a vaccine.10

Because mumps is “rarely fatal” there haven’t been many opportunities to study autopsy tissue and so, “our current knowledge of MuV [mumps virus] pathogenesis is therefore mostly based on animal studies, often following unnatural routes of infection. Consequently, the pathogenesis of the virus in humans remains in question.” Pathogenesis is how a disease develops; in other words, doctors and scientists don’t really know how mumps works.11

Are there benefits to uncomplicated childhood mumps?

In childhood, mumps is relatively mild. But after puberty, especially for males, mumps can be associated with many complications including sterility. Therefore, if our vaccines don’t last very long, we’re creating a situation where vaccination is less safe overall and riskier than acquiring the disease naturally, as 95% of American children did historically.

As cited in our article on measles, a 2015 study concluded that people who had measles and mumps in childhood had lower risk of cardiovascular disease, and men who had mumps were less likely to die from stroke.12 A 2007 study in the journal Atherosclerosis also found that mumps and other typical childhood diseases such as measles, rubella, and chicken pox, increased a protective effect against acute coronary events.13

Notably, “Miller’s Review of Critical Vaccine Studies” summarizes 11 peer–reviewed, published studies that found a history of childhood mumps could protect against various cancers later in life (and one study specifically found no protection in those vaccinated against mumps).14

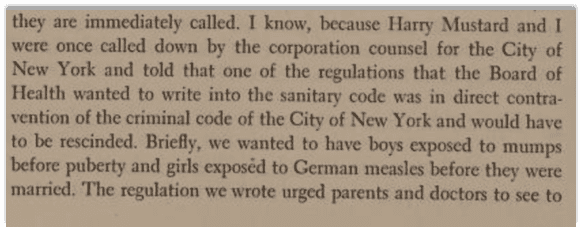

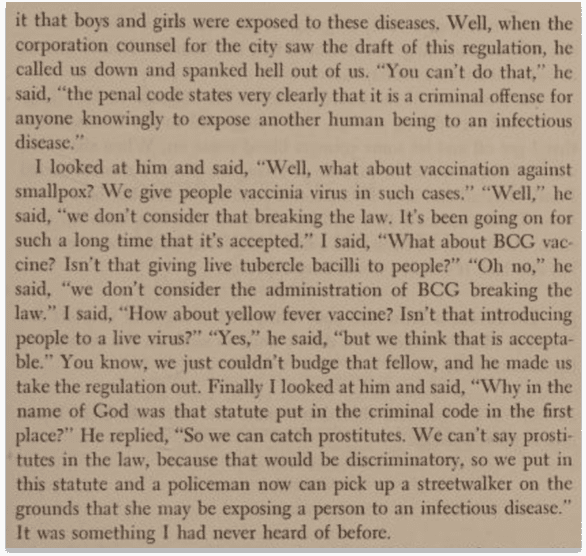

You may be shocked to discover that one of the pioneers in the field of virology, Dr. Tom Rivers, was a proponent of intentional exposure to mumps and rubella to induce natural immunity and avoid complications from infection later in life. As recounted in the book “Vaccine” by Arthur Allen, “In the 1930s, Tom Rivers wanted the New York Division of Health to require parents to ‘see to it that boys and girls were exposed’ to mumps and rubella,” until the city told him it was against criminal law.15 Rivers recounted the situation in an oral history.16

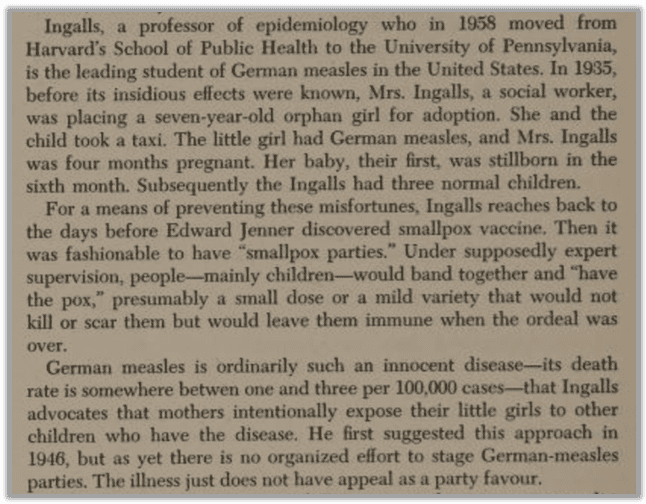

Rivers was not alone in this sentiment. Arthur Allen further describes University of Pennsylvania professor Theodore Ingalls’ advocacy for the city of Philadelphia to “organize chickenpox and rubella parties so children could be exposed in a controlled way.”17 As described in “Virus Hunters” by Greer Williams:18

(Interestingly, Ingalls tipped off researchers to a measles outbreak at the Fay School in Massachusetts, which led to the Edmonson strain being discovered and developed into the first measles vaccine.)

Ingalls continued to be a proponent of exposing young girls to rubella, before the vaccine was developed, though it appears he also believed vaccine immunity and natural immunity would be the same.19

Mumps vaccine development

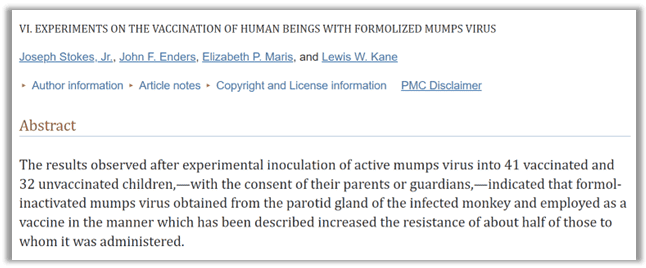

As far back as the 1940s, researchers with the Armed Forces Epidemiological Board had created experimental mumps vaccines.20 During WWII, Dr. John Enders was recruited to work on mumps vaccines, given that mumps infection in the military would reduce the number of available men.

As described in our articles on measles and RSV, it was common practice to test experimental vaccines on children, especially children in state custody in places like foster homes and facilities for the disabled. No vaccine from Enders’ work was licensed for public use.

Mumps, like the measles vaccine, was created not because of an urgency or need from parents and doctors, but instead, simply because it could be done, and Cold War scientists were caught up in the excitement of asserting American dominance in science. No one was asking for a mumps vaccine when Dr. Maurice Hilleman began its development at Merck. The situation was pure chance and opportunity.

Immediately on the heels of creating the measles vaccine, Hilleman’s daughter got a case of the mumps. As the story goes, she woke him in the middle of a March night in 196321 with a sore throat. Hilleman quickly realized she had the mumps, so he ushered his child back to bed, then rushed to his laboratory at Merck. He obtained sampling equipment, drove back home to his sleeping daughter, woke her to swab her throat, and took the specimen back to Merck’s freezer before going back to sleep at home.

Paul Offit interviewed Hilleman in the months before his death and published the man’s history in vaccine development in the 2007 book “Vaccinated.” Here’s how the biographer described the development of the mumps vaccine:

Editor’s note: This passage contains graphic descriptions of the use of animals in vaccine research. It is included to give the readers a glimpse of typical vaccine development techniques still in use today.

“When he got back to his laboratory, he took the broth containing Jeryl’s (Maurice’s daughter) virus and inoculated it into an incubating hen’s egg; in the center of the egg was an unborn chick. During the next few days the virus grew in the membrane that surrounded the chick embryo. Hilleman then removed the virus and inoculated it into another egg. After passing the virus through several different eggs, Hilleman tried something else. He took an egg that had been incubating for twelve days and removed the gelatinous, dark brown chick embryo. Typically it takes about three weeks for an egg to hatch, so the embryo was still very small, weighing about the same as a teaspoon of salt. Hilleman cut off the head of the unborn chick, minced the body with scissors, treated the fragments with a powerful enzyme, watched the chick embryo dissolve into a slurry of individual cells, and placed the cells into a laboratory flask. (A cell is the smallest unit in the body capable of functioning independently. Human organs are composed of billions of cells.) Chick cells soon reproduced to cover the bottom of the flask. Hilleman passed Jeryl Lynn’s mumps virus from one flask of chick cells to the next and watched as the virus got better and better at destroying cells. He repeated this procedure five times.

Hilleman reasoned that as his daughter’s virus adapted to growing in chick cells, it would get worse at growing in human cells. In other words he was trying to weaken his daughter’s virus. He hoped that the weakened mumps virus would then grow well enough in children to induce protective immunity, but not so well that it would cause the disease. When he thought the virus was weak enough…Hilleman then made a choice that was typical of the time but abhorrent today: they decided to test their experimental mumps vaccine in developmentally disabled children.”

Hilleman followed in the footsteps of his scientific kin, testing the experimental mumps vaccine on developmentally disabled children. In 1967, Hilleman teamed up with other medical researchers to test his live-but-weakened (known as “attenuated”) vaccine on children institutionalized for developmental disabilities in the Trendler Nursery School and Merna Owens Home in Pennsylvania.xxii As Offit describes in the biography, Hilleman was “unrepentant” about this testing. His justification was that most children get the mumps and developmentally disabled children shouldn’t be denied the chance to avoid it with his vaccine. The “children are perceived as more helpless; but their understanding of the shot that they were given, and their willingness to participate in the trial was no different than [that of] healthy babies and young children. The difference was that [developmentally disabled] children were often wards of the state; their rights weren’t protected by their parents.”22

To get a larger sample size, they passed out flyers at kindergartens and schools around Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and held informational meetings at churches.23

“Hilleman remembered a parent asking how the vaccine was made. Joe Stokes answered the question. Handsome, with silver-gray hair and the gentle spirit of his Quaker background, Stokes told the story of a German man who had left his wedding ring on a nightstand. During the night a spider made a dense, intricate web by going back and forth, side to side. By the morning the web had covered the entire opening in the ring. ‘He was trying to explain what chick cells looked like when they grew in laboratory flasks,’ recalled Hilleman. ‘He called it Gewebekulter— web culture. Jesus, they were spellbound.’”24

Ultimately, this vaccine was licensed as the Jeryl Lyn strain, named after Hilleman’s daughter.

Until COVID shots, the mumps vaccine had the distinction of being the fastest vaccine to come to market, in only four short years.

Mumps vaccine effectiveness

Does the mumps vaccine work? You don’t have to dig too far to find evidence questioning how effective it is or how long immunity lasts.

It is widely accepted in the medical community that the efficacy of the mumps vaccine is questionable at best. In 2016 and 2017, there was an outbreak of mumps in Boston,25 despite high levels of vaccination. This outbreak was preceded by a series of outbreaks in highly vaccinated populations over years.

A 2015 summary of current knowledge of mumps and its vaccine stated:

“However, within a few years of these historic lows [after the vaccine was introduced], large, sporadic mumps outbreaks began to appear globally, involving a high percentage of persons with a history of vaccination. The reason for the lower-than-expected efficacy of mumps vaccines is a subject of much debate, ranging from waning immunity to the emergence of virus strains that might be capable of escaping immunity engendered by the vaccine.”26

From Clinical Infectious Diseases journal, 2015:27

From the New York Times, 2018:28

Two Merck scientists filed a whistleblower lawsuit against Merck in 2010 for falsifying data about mumps vaccine efficacy.29 This case is important not just for informed consent, but also for American tax dollars. Merck is the sole provider of the mumps vaccine and claims 95% efficacy.30 The CDC purchases shots with mumps in it for the Vaccines for Children (VFC) program, which distributes immunizing agents to poor children.31

After 13 years of discovery and many attempts by Merck to get the case thrown out, a federal district court dismissed the case.32 Merck didn’t get the case thrown out because they were able to prove they were truthful about their claim that the vaccine is 95% effective; the company won because the federal government would purchase it anyway, even if the whistleblowers are right.

An appeal was filed in the Third Circuit Court of Appeals and, as of March 2024, is not yet decided.33

In addition to how long efficacy lasts, there is question of how much the vaccine can protect against. The European Center for Disease Prevention and Control tells us, “[s]everal different genotypes of the mumps virus have been recognized, although the significance of this genotypic variation with regards to vaccine response remains unclear.”34 This means scientists aren’t sure if the vaccine will prevent different strains of mumps.

Safety concerns with the mumps vaccine

The worst thing about the known and accepted waning mumps efficacy is that the shot stops working at the worst possible time: adolescence. Acquiring mumps in adolescence or young adulthood is particularly difficult for males, who have the chance of inflammation of the testicles which can affect fertility.35

Three studies summarized in “Miller’s Review of Critical Vaccine Studies” found a possibility of increased risk of developing Type 1 diabetes associated with the mumps vaccine.36

One 2015 publication describes: “In addition to questions over vaccine efficacy, safety concerns have come to light following reports of meningitis linked to some vaccine strains used outside the USA. This has led to withdrawal of some vaccine strains and, in some cases, complete cessation of mumps vaccination. In Japan, for example, mumps vaccination was removed from the national immunization programme.”37

There’s also evidence of the Jeryl Lyn strain of mumps from the MMR vaccine being found in a child who died from brain swelling (encephalitis) after vaccination.38

Conclusion

Mumps was so little a concern to Americans that the CDC didn’t track it as a notifiable disease. Acquiring the illness was a rite of passage in childhood and well accepted by parents. Death and complications in young children were rare.

So why do we have a mumps vaccine?

Because Maurice Hilleman made it, and Merck wanted to sell it.

But more than anything, vaccines are a valuable tool because they sell fear. Fear of illness, fear that our bodies can’t handle things we encounter.

We have been taught to see illness as an enemy to be conquered. And we have been conditioned to forget that struggles in life transform us into stronger people. They also connect us to other humans through compassion for those on the journey and camaraderie for those who have undergone the same.

No parent wants their child to suffer. “Yet, in reality, complete freedom from disease and from struggle is almost incompatible with the process of living.”39

These words from the 1959 book “Mirage of Health” put illness into perspective well:

“Life is an adventure in a world where nothing is static; where unpredictable and ill-understood events constitute dangers that must be overcome, often blindly and at great cost; where man himself, like the sorcerer’s apprentice, has set in motion forces that are potentially destructive and may someday escape his control. Every manifestation of existence is a response to stimuli and challenges, each of which constitutes a threat if not adequately dealt with. The very process of living is a continual interplay between the individual and his environment, often taking the form of a struggle resulting in injury or disease.”

Does it affect your view of the mumps vaccine to know that it wasn’t asked for by the people? That mumps is not a deadly virus and it does not cause epidemics? That the vaccine’s failure to protect our children is so well understood it’s openly acknowledged in peer-reviewed publications? And that there are questions about its safety so serious it has been removed from recommendations in other countries?

This is the kind of information your doctor can’t tell you when they ask for your informed consent to push this pharmaceutical into your baby’s arm. When parents look at risks and benefits, we must balance that analysis for both the illness and the intervention.

What happens if I say yes to this shot? What are the chances of a good or bad outcome? How good or bad could it be?

What happens if I say no? What are the chances of a good or bad outcome? How good or bad will that be?

By reading this and the other articles in our Health Freedom Institute series on childhood immunizations, you’re now able to see how treatments that are claimed to have been created exclusively by science can be swayed by profit, politics, and fear. Never forget that the decision to vaccinate is moral and individual judgment at its core.

References

- Rubin, Steven, Michael Eckhaus, Linda J. Rennick, Connor G. Bamford, and W. Paul Duprex. “Molecular Biology, Pathogenesis and Pathology of Mumps Virus.” The Journal of Pathology 235, no. 2 (2015): 242-252. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4268314/. ↩︎

- Marlow, Mariel PhD, MPH, Penina Haber MPH, Carole Hickman PhD, and Manisha Patel MD, MS. “Mumps.” The CDC Pink Book, no. 14th Edition (2021). https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/mumps.html#:~:text=persons%20fully%20vaccinated-,Secular%20Trends%20in%20the%20United%20States,3%2C000%20cases%20were%20reported%20annually. ↩︎

- Flores, John MD, and Lilly Cheng Immergluck MD, MS, FAAP. “Measles Update in an Era of Vaccine Hesitancy and Global Pandemic.” Pediatrics in Review, (2023). https://publications.aap.org/pediatricsinreview/article-abstract/44/9/529/193780/Measles-Update-in-an-Era-of-Vaccine-Hesitancy-and?redirectedFrom=fulltext?autologincheck=redirected. ↩︎

- Marlow, Mariel PhD, MPH, Penina Haber MPH, Carole Hickman PhD, and Manisha Patel MD, MS. “Mumps.” The CDC Pink Book, no. 14th Edition (2021).

https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/mumps.html#mumps-virus ↩︎ - Marlow, Mariel PhD, MPH, Penina Haber MPH, Carole Hickman PhD, and Manisha Patel MD, MS. “Mumps.” The CDC Pink Book, no. 14th Edition (2021).

https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/mumps.html#mumps-virus ↩︎ - ↩︎

- Johnson, Claud D., and Ernest W. Goodpasture. “AN INVESTIGATION OF THE ETIOLOGY OF MUMPS.” The Journal of Experimental Medicine, (1934). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2132344/. ↩︎

- Summers, William C. “Inventing Viruses.” PubMed, (2014): 27. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26958713/. ↩︎

- Summers, William C. “Inventing Viruses.” PubMed, (2014). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26958713/. ↩︎

- Habel, Karl. “Public Health Reports.” CDC Stacks 60, no. 8 (1945). https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/70503.

↩︎ - Rubin, Steven, Michael Eckhaus, Linda J. Rennick, Connor G. Bamford, and W Paul Duprex. “Molecular Biology, Pathogenesis and Pathology of Mumps Virus.” The Journal of Pathology 235, no. 2 (2015): 242-252. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4268314/. ↩︎

- Kubota, Yasuhiko , Hiroyasu Iso , Akiko Tamakoshi, and JACC Study Group. “Association of Measles and Mumps with Cardiovascular Disease: The Japan Collaborative Cohort (JACC) Study.” Atherosclerosis 241, no. 2 (2015): 682-686. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26122188/.

. As summarized in Miller’s Review of Critical Vaccine Studies, page 140. ↩︎ - Pesonen, Erkki, et al. “Dual Role of Infections as Risk Factors for Coronary Heart Disease.” Atherosclerosis 192, no. 2 (2007): 370-375. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16780845/.

As summarized in Miller’s Review of Critical Vaccine Studies, Page 150. ↩︎ - Miller, Neil Z. 2016. Miller’s Review of Critical Vaccine Studies. 1st ed. New Atlantean Press,

, page 229-232, 235, 238-240, 247 ↩︎ - Allen, Arthur. 2008. Vaccine: The Controversial Story of Medicine’s Greatest Lifesaver. W. W. Norton & Company, page 218. ↩︎

- Rivers, Tom. 1967. Reflections on a Life in Medicine and Science. The M.I.T. Press. https://archive.org/details/tomriversreflect0000unse/mode/2up, page 394. ↩︎

- Allen, Arthur. 2008. Vaccine: The Controversial Story of Medicine’s Greatest Lifesaver. W. W. Norton & Company, page 218. ↩︎

- Williams, Greer. 1960. Virus Hunters. Hutchinson of London. https://archive.org/details/virushunters0000unse/mode/2up. ↩︎

- Medicine: Catch German Measles.” Time, December 31, 1956. https://content.time.com/time/subscriber/article/0,33009,867505,00.html. ↩︎

- Stokes, Joseph Jr., et al. “Immunity in Mumps.” Journal of Experimental Medicine, (1946). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2135664/. ↩︎

- Offit, Paul A. 2022. Vaccinated: From Cowpox to MRNA, the Remarkable Story of Vaccines. Harper Perennial,

page 20. ↩︎ - Offit, Paul A. 2022. Vaccinated: From Cowpox to MRNA, the Remarkable Story of Vaccines. Harper Perennial, page 25 ↩︎

- Offit, Paul A. 2022. Vaccinated: From Cowpox to MRNA, the Remarkable Story of Vaccines. Harper Perennial, page 29. ↩︎

- Offit, Paul A. 2022. Vaccinated: From Cowpox to MRNA, the Remarkable Story of Vaccines. Harper Perennial, page 29. ↩︎

- Zusi, Karen . “New Details about Mumps Outbreaks of 2016‒17.” Harvard Gazette, February 11, 2020. https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2020/02/the-story-behind-the-mumps-outbreaks-of-2016-17/. ↩︎

- Rubin, Steven, Michael Eckhaus, Linda J. Rennick, Connor G. Bamford, and W Paul Duprex. “Molecular Biology, Pathogenesis and Pathology of Mumps Virus.” The Journal of Pathology 235, no. 2 (2015): 242-252. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4268314/. ↩︎

- Clemmons, Nakia S., et al. “Characteristics of Large Mumps Outbreaks in the United States, July 2010-December 2015.” Clinical Infectious Diseases 68, no. 10 (2018). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30204850/. ↩︎

- Klasco, Richard M.D. “How Long Do I Retain Immunity?” The New York Times, September 21, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/21/well/live/immunity-vaccines-measles-mumps-tetanus-vaccination.html. ↩︎

- “United States v. Merck & Co., 44 F. Supp. 3d 581 (E.D. Pa. 2014).” (2014). https://www.courtlistener.com/opinion/7308574/united-states-v-merck-co/. ↩︎

- Helfand, Carly. “Lawsuits Claiming Merck Lied about Mumps Vaccine Efficacy Headed to Trial.” Fierce Pharma, September 9, 2014. https://www.fiercepharma.com/infectious-diseases/lawsuits-claiming-merck-lied-about-mumps-vaccine-efficacy-headed-to-trial. ↩︎

- Kramer, Reuben. “Class Says Merck Lied About Mumps Vaccine.” Courthouse News Service, June 27, 2012. https://www.courthousenews.com/class-says-merck-lied-about-mumps-vaccine/. ↩︎

- “United States v. Merck & Co.” (2023). https://casetext.com/case/united-states-v-merck-co. ↩︎

- “Stephen Krahling, Et Al V. Merck & Co Inc.”, September 5, 2023. https://dockets.justia.com/docket/circuit-courts/ca3/23-2553. ↩︎

- “Factsheet about Mumps.” European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/mumps/facts. ↩︎

- “Complications of Mumps.” CDC Website https://www.cdc.gov/mumps/about/complications.html. ↩︎

- Miller, Neil Z. 2016. Miller’s Review of Critical Vaccine Studies. 1st ed. New Atlantean Press, page 198. ↩︎

- Rubin, Steven, Michael Eckhaus, Linda J. Rennick, Connor G. Bamford, and W Paul Duprex. “Molecular Biology, Pathogenesis and Pathology of Mumps Virus.” The Journal of Pathology 235, no. 2 (2015): 242-252. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4268314/. ↩︎

- Morfopoulou, Sofia, et al. “Deep Sequencing Reveals Persistence of Cell-associated Mumps Vaccine Virus in Chronic Encephalitis.” ResearchGate, (2017). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/309362332_Deep_sequencing_reveals_persistence_of_cell-associated_mumps_vaccine_virus_in_chronic_encephalitis. ↩︎

- Dubos, Rene. 1987. Mirage of Health: Utopias, Progress, and Biological Change. Rutgers University Press,

page 1. ↩︎